We all know that it’s essential to exercise regularly, but many of us also struggle with our sedentary lifestyles. Unfortunately, the evidence is mounting to describe the adverse outcomes associated with sitting too much, whether in our work or leisure. Read on to find out why walking less than 4000 steps per day could prevent you from experiencing many of the positive effects of exercise and discover what you can do about it.

‘Exercise is medicine’. Fortunately, I enjoy exercise and can usually fit in four or more workouts a week. However, my main struggle is with sedentary behaviour. Like many people, my job involves a lot of sitting and screen time. The worst days are when I work from home. From a productivity perspective, it’s excellent, but I can easily spend a day accumulating less than 3000 steps. There’s a reason that step counts and sedentary time are big concerns in the context of workplace wellbeing.

A Dose-Response Relationship Between Sitting & Dying

The importance of step-counts can be overstated, but they do provide a useful measure, particularly as a way to get a simple insight into how active someone has been for the day. If your accumulating steps, you are not sitting, which is likely a good thing. There is a dose-response association between total sitting time and all-cause mortality1. Basically, the longer you sit, the higher the risk of dying from anything. Also, unfortunately, sitting appears to be an independent risk factor2. Even if you exercise regularly, it doesn’t seem that you can inoculate yourself against physical inactivity. What is worse, being sedentary may reduce the positive benefits of exercise, when you get around to your workout3.

Investigating The Effects Inactivity On Exercise Benefits

In 2019, a group of researchers set out to investigate the effects of inactivity on the metabolic benefits of an exercise session. When someone exercises, we expect to see a positive change in the fat that is circulating in the bloodstream (fewer triglycerides), the amount of sugar (less glucose), and the body’s insulin response (an indicator of how well the body can maintain blood sugar in a healthy range). The researchers hypothesised that being sedentary for a few days before an exercise session may have an adverse impact on these measures.

To test this, the scientists recruited a group of participants who were healthy, without a history of cardiovascular or metabolic disease, not taking medications and were untrained to recreationally active, in terms of their levels of fitness. On the first three days of the study, participants were sedentary/inactive, which mean that they ‘achieved’ more than 13 hours per day of sitting time. On day four, each participant completed either 1) a fourth day of sedentary/inactive behaviour or 2) a fourth day of sedentary/inactive behaviour, with the addition of 1 hour of moderate-intensity treadmill exercise (60-65% of V̇O2max.)

The People Who Sit The Most Benefit The Least

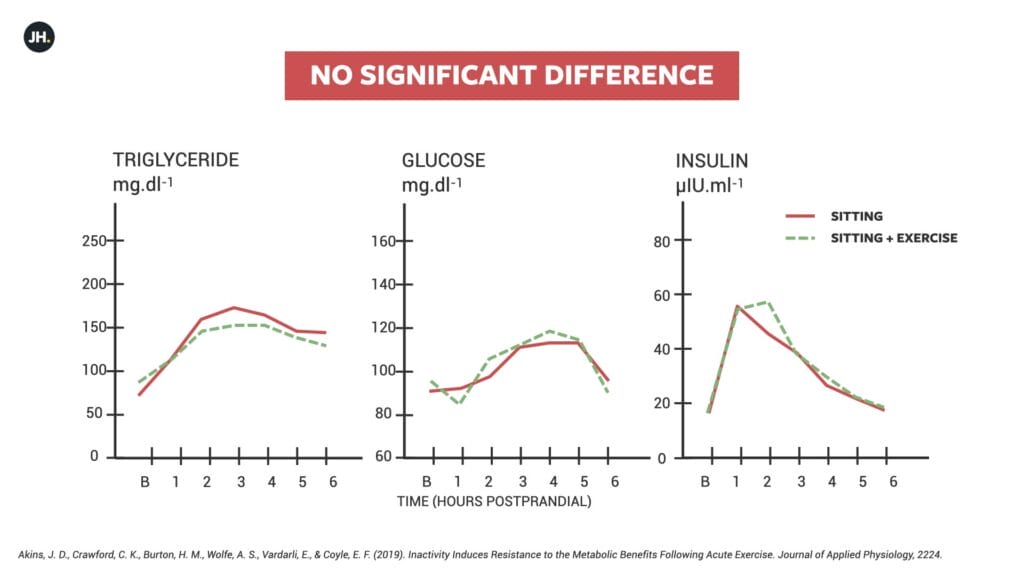

The researchers reported that there were no statistically significant differences in triglycerides, blood glucose or insulin response in the group who exercised at the end of the four days of sedentary behaviour, relative to the group who did not exercise.

The researchers concluded that these results indicate that physical inactivity (sitting for around 13.5 hours a day, accumulating less than 4,000 steps, created a condition whereby the participants became ‘resistant’ to the metabolic improvement that typically results from aerobic exercise.

The people who sit the most appear to benefit the least from exercise.

Stay Active, No Matter How Much Your Workout

The results of this study, and the earlier work which describes the dose-response relationship between sitting and death, make for sobering reading, with a simple application. Regardless of how often you exercise, simply moving more during the day could be an effective way to:

- Improve your health

- Enhance longevity

- Protect your body’s response to exercise

Also, as I’ve described in earlier articles, compared to uninterrupted sitting, standing or walking, even for short periods, may improve your cognitive performance. While I don’t think that wearables are the answer to everything, I encourage you to keep a track of your daily steps for a few weeks, try to accumulate over 4,000 per day, ideally by standing up and moving around regularly (as opposed to gathering them all in a single session), and see how you feel. It will likely benefit your short term performance and long-term health.

- References

- Diaz KM, Howard VJ, Hutto B, Colabianchi N, Vena JE, Safford MM, et al. Patterns of sedentary behaviour and mortality in U.S. middle-aged and older adults: A national cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;167(7):465–75.

- Bouchard C, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (2015) Less Sitting, More Physical Activity, or Higher Fitness? Mayo Clin Proc 90,1533-1540

- Akins, J. D., Crawford, C. K., Burton, H. M., Wolfe, A. S., Vardarli, E., & Coyle, E. F. (2019). Inactivity Induces Resistance to the Metabolic Benefits Following Acute Exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2224.